Un tempo centro delle macchine con motore a combustione, la regione di Stoccarda sta ora diversificando le sue opzioni di mobilità. L'integrazione di veicoli elettrici, superblocchi, Fahrradstraßen (ciclabili) e sistemi di trasporto pubblico migliorati offre ai cittadini soluzioni sostenibili, adattate alle loro esigenze. Questa rivoluzione, però, si trova ad affrontare sfide significative, con la scarsità di risorse che emerge come una preoccupazione principale (articolo in inglese).

Baden-Württemberg: From Car-Centric to Multi-Modal Mobility

Stuttgart is the capital of Baden-Württemberg, one of the 16 federal states of the Federal Republic of Germany. Located in the Neckar Valley in the southwest of the country, the city has a population of around 630,000 and serves as a key hub for the automotive industry, housing major manufacturers such as Mercedes-Benz, Audi, and Porsche. These companies maintain significant factories and museums in and around the city, which continues to be a centre for engineering and technological innovation.

This long-standing tradition as a centre for car production brings both advantages and challenges. On the one hand, the automotive industry has historically positioned the city as a leader in innovation; on the other hand, it has also contributed to serious environmental issues, including pollution, traffic congestion, and climate change.

One growing concern is the rising cost of the cars produced. For instance, the Audi plant in Neckarsulm primarily manufactures high-end models like the Audi A8, which are unaffordable for most consumers. These vehicles, predominantly black, are mainly targeted at institutional clients or the Chinese market.

Moreover, Stuttgart and Germany are losing their competitive edge in car production, a sector where they have traditionally excelled. As a matter of fact, Germany appears to be falling behind in the transition to electric vehicles, a field where China has taken the lead. This global shift raises significant questions about the future of mobility and sustainability in Stuttgart and other industrial cities, challenging the economic model that has been built around luxury cars.

Stuttgart and the whole region are in a transformation from being centred around combustion engine cars to becoming a city for different sustainable means of mobility. The travelling platform “tripz” did a ranking of the cities with the best public transport in Germany. Stuttgart got the fourth place in the ranking of the 25 most populous cities in Germany.

Mobility usage has changed in recent years in Stuttgart. In 2000, 45 % of trips were done by car, 28 % by foot, 5 % by bike, and 21 % by public transport. In 2023, new numbers showed that car trips dropped by around one third. Foot increased by 8 percentage points. Bike trips more than doubled, and the share of public transport only rose marginally.

The reduction of the maximum speed in Stuttgart from 50 to 40 km/h in Stuttgart might be one of the reasons behind this development. Moreover, 60 % of the streets have an even lower speed limit of 30 km/h.

Revolutionising Streets: From Car-Dominated Roads to Fahrradstraßen

In the city’s transformation toward sustainable mobility, streets also play a key role. Once dedicated exclusively to automobiles, they are now being reimagined as spaces designed for bikes as well—granting all citizens, not only drivers, the right to access public land.

This change is taking shape through wider and safer bike lanes, designed to protect cyclists moving alongside cars. In some cases, the transformation is even more radical: It goes beyond making streets bike-friendly and aims to redesign them as bicycle-first spaces exclusively for bicycles and pedestrians.

Stuttgart, like many other German cities, has “Fahrradstraßen” or “bicycle streets”. These are the same streets that, until a few years ago, were reserved exclusively for car traffic. Now, cyclists have priority: They can ride side by side, occupy the entire roadway, and set the pace of traffic. Other vehicles, whose transit is sometimes permitted under specific conditions, must adapt to the presence, pace, and space of cyclists—not the other way around. Not anymore.

The Elephant in the Room for Policymakers: The Scarcity of Resources

One major challenge in addressing mobility issues is the effective allocation of resources, particularly time and money. While some projects may seem promising for advancing sustainable mobility, they often require substantial public funding and significant time to realize. If such projects are designed to reduce emissions, they might initially generate considerable emissions during construction, taking years to offset before they begin to contribute to overall reductions.

This is evident in Stuttgart's controversial Stuttgart 21 project, a large railway initiative aimed at connecting high-speed rail from Stuttgart to Ulm, with plans to extend to Munich in the future. Announced around 40 years ago, the project is expected to be completed in a few years. It has polarized public opinion due to its complexity and perceived lack of communication among stakeholders, including politicians, civil society, and the construction entities involved. Critics have raised concerns about skyrocketing costs—now at €15 billion—that could have been allocated to more urgent projects, alongside the lengthy delays in its completion.

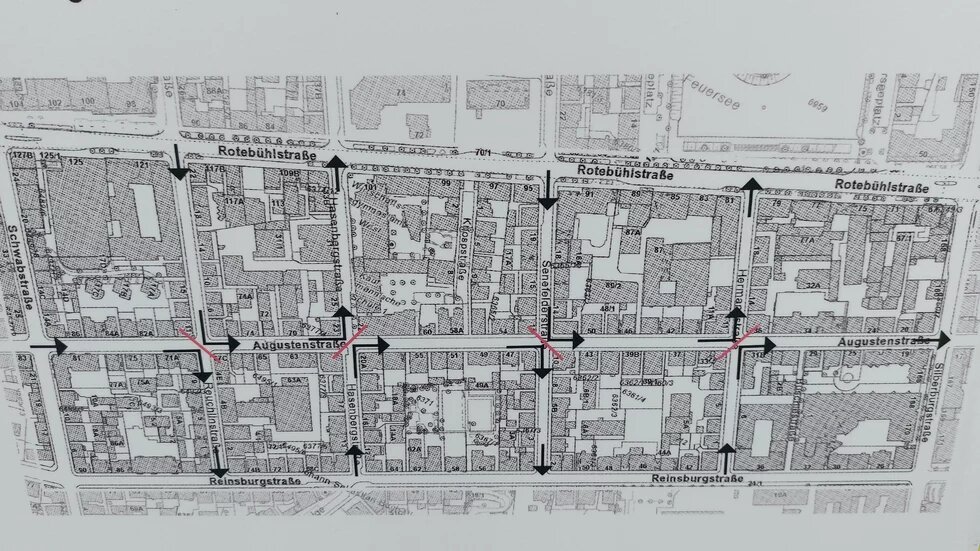

Another example illustrating the challenges of short-term political approaches is Stuttgart's Superblock initiative. This project aims to reduce traffic in specific districts through various measures, such as lowering speed limits and redesigning streets to include green spaces for community gathering. However, the Superblock has faced criticism for its high costs and limited quality of greenery, as it was implemented as a temporary measure. Plants were rented and placed in pots instead of being planted in the ground, creating management challenges and affecting their sustainability.

These examples highlight the need for a long-term political vision to ensure that mobility projects are not only sustainable but also cost-effective and beneficial for the community.

Mobility and Traffic: What Is the Difference?

It is important to distinguish between mobility and traffic, as they refer to different aspects of transportation. Mobility is about how easily people can move around and access different places, focusing on the availability and convenience of various transportation options. It encompasses all forms of travel—walking, biking, using public transit, and driving—and emphasizes the overall experience of getting from one location to another.

On the other hand, traffic specifically refers to the movement of vehicles on roadways. It often highlights issues like congestion, delays, and the environmental impact of cars and trucks. Traffic primarily deals with the flow and management of vehicles, often concentrating on reducing bottlenecks and improving road conditions.

As urban populations grow, the demand for mobility is likely to increase, creating new challenges for city planners and policymakers. The public sector has a key role in making the transition to more sustainable forms of mobility. This includes investing in infrastructure that supports walking, cycling, and public transportation, as well as promoting electric vehicles and ride-sharing options.

In the European Union, transportation accounted for about 29% of all greenhouse gas emissions in 2022. Despite efforts to cut these emissions, progress has been slow, which raises important questions about the future of transportation infrastructure. Should public transport systems, like railways, remain under government control to ensure fair access and focus on sustainability? Or would competition in the private sector lead to better services and innovation?

Ultimately, the answers to these questions will significantly shape the future of mobility and the effectiveness of strategies aimed at reducing traffic-related emissions while meeting the growing demand for transportation options.

Public Transport: How Can We Nudge People to Increase Usage?

A common concept in Germany is the public transport “job ticket,” where employers contribute to the costs of monthly public transport passes for their employees. Because employers purchase these tickets in bulk, the “job ticket” typically offers a discount (usually around 5%) compared to buying the ticket individually. There is also a job version of the “Deutschlandticket,” which allows users to access nearly all public transport in Germany, excluding long-distance trains. Some employees, such as those in the Stuttgart city administration, receive this ticket fully funded by their employer.

Additionally, a subsidized “Social ticket” is available for low-income households in cities like Stuttgart. Depending on the specific implementation, this ticket may be valid only within the local transport association or extend beyond it. In Baden-Württemberg, there is also a youth ticket, introduced at an annual price of €365, which has now been integrated into the Deutschlandticket. With the general price increase of the Deutschlandticket to €58 per month in 2025, the youth ticket will also see a price rise. In Hamburg, since September 2024, all students can receive a Deutschlandticket for free.

Furthermore, the city of Stuttgart offers subsidies for electric cargo bikes for families. Since the project began in 2018, around 1,700 families have applied for this subsidy, which provides €600 to each family with at least one child. This subsidy is also applicable for leasing contracts. Additionally, families can receive a “sustainability bonus” if they do not register a car in their household for three years following the purchase. Lower-income households can receive total subsidies of up to €2,600.

Some cities offer a free public transport pass in exchange for relinquishing a driving license, although this is often limited to one year rather than being unlimited. This approach may be less effective in rural areas compared to urban settings.

In general, programs aimed at encouraging the use of more environmentally friendly transport modes tend to conclude after a few years. For greater effectiveness, reliable long-term funding for these initiatives is essential.